#54 - You should hold on a bit more when you feel like releasing

You should hold on a bit more when you feel like releasing. And no, I am not talking about sex.

Okay, that was a clickbait-y title, but now that I've got your attention: this blog post is not about sex, it's about thinking.

Have you ever noticed how, when you’re thinking through a tough problem, there’s always a moment when the whole thing starts to feel a little uncomfortable? Not because the problem is impossible, but because your mind has held it long enough that the easy angles are exhausted. That’s usually when the urge to release kicks in - close the tab, ship the feature, publish the half-formed post, or simply move on. Over the years, especially in my product work, I’ve realized that this moment is weirdly consistent: it shows up right before the thinking gets interesting.

I didn’t always understand why, but lately I’ve been trying to make sense of this pattern - why the best framings seem to appear only after I push past that small internal pressure. This essay is my attempt to unpack that experience, and why holding on just a bit longer tends to lead somewhere worth going.

Think long and hard about stuffs

On long thinking as a concept

In the recent episode of his podcast, Cal Newport tells a story about "The Beast." It was the early 2000s, before smartphones commanded our attention at every idle moment, and Newport - then a graduate student - was wrestling with a particularly difficult theorem. He discovered new ways to tackle the theorem during a walk towards his university campus by engaging in long thinking - the act of directing sustained attention at a difficult problem for an extended period of time.

Here's the relevant transcript from that episode for reference (emphasis mine):

Instead, I decided to log some hard focus hours on what I called the Beast—a particularly vexing theory problem that my collaborators and I had been battling for months. (As an aside, I used the term “hard focus” here before I started using the phrase “deep work.”)

I grabbed some coffee and headed toward the Berkeley campus on foot. It was early, and the fog was just starting to march down from the Berkeley Hills. I eventually wandered into a eucalyptus grove—here’s a photo of that same grove, not mine, but it’s where I ended up that morning.

Once there, I sipped my coffee and thought. Our existing strategy for the Beast involved a complicated algorithm that none of us looked forward to analyzing. Deploying a trick I had learned in grad school, I avoided the need to understand why the complicated algorithm worked by turning my attention instead to why simpler strategies failed.

After about an hour—which included a strategic refill at the Free Speech Café—I had an idea for a more concise and easier-to-analyze algorithm that seemed to work. But I realized there’s a limit to how deep you can go when keeping an idea only in your mind. To capture the insight more concretely, and inspired by my recent commitment to what I called the “textbook method,” I walked to a nearby CVS and bought a 6x9 stenographer’s notebook.

I then forced myself to write out my thoughts more formally. Here’s a photo of my notes from that day. Looking at those diagrams now, I can’t quite recall the details, but it seems like it was related to the local model of distributed communication. Still, the combination of pen-and-paper notes with the abstract content I was working through unlocked new layers of understanding."

Regain Your Ability to Think (in 60 Minutes a Week) | Cal Newport

This story resonates with me a lot. For those of you who don't personally know me, I am a somewhat solitary creature, except towards close friends and family. I tend to enjoy doing things alone. My profession is Product Management which revolves around solving hard problems pretty much all day. You need to have an active physical life to continuously and intensely participate in problem-solving, and my go-to exercise has always been either walking or running.

When I run, I listen to podcasts such as Cal Newport's, high-tempo music to match my jogging pace, or David Goggins shouting "Stay hard" or "Who's gonna carry the boat" (if you know, you know). But sometimes I just want to enjoy a slow walk - during which I often do long thinking - circling around, hammering at, and meditatively holding a particular problem in mind for hours. You'd be surprised at how often good framings/insights spring out of this type of physical & mental exercise (It's quite often).

A specific example on how long thinking helped me

Let me tell you an example about such a light bulb moment: I'm building a product called Garden, and our focus is on helping product professionals improve and showcase their product thinking to hiring managers. We have a power user - a junior PM, who's been leveraging the product for their product initiative at work. She was able to use the product to identify assumptions and reduce uncertainties via learnings.

But what about our students in the Breaking into Product Management (BPM) course - those that are just getting started in their product careers? Obviously, as founders of the course, we do want to leverage BPM distribution to attract Alpha users for our new product, which raises the question: can our BPM students leverage Garden to complete their intensive two-week final projects more effectively?

Naturally, my first thought was to just let them use it and gather feedback. However, if you've ever built a product from scratch, you'd know first-hand how confusing feedback can be. Typically, some people find values and others don't. If you don't have a good theory to make sense of the feedback, you'd be drowned in mixed signals.

Over time, I've learned to attempt to articulate why it would or wouldn't work before actually validating with MVPs and whatnot. That also goes for this as well. From a first-principle thinking perspective, I wanted to conceptualize a theory that would help me predict whether that BPM students can indeed benefit from Garden. The point wasn't to just use it to predict behaviors, but to make sense of the feedback and adjust my theory.

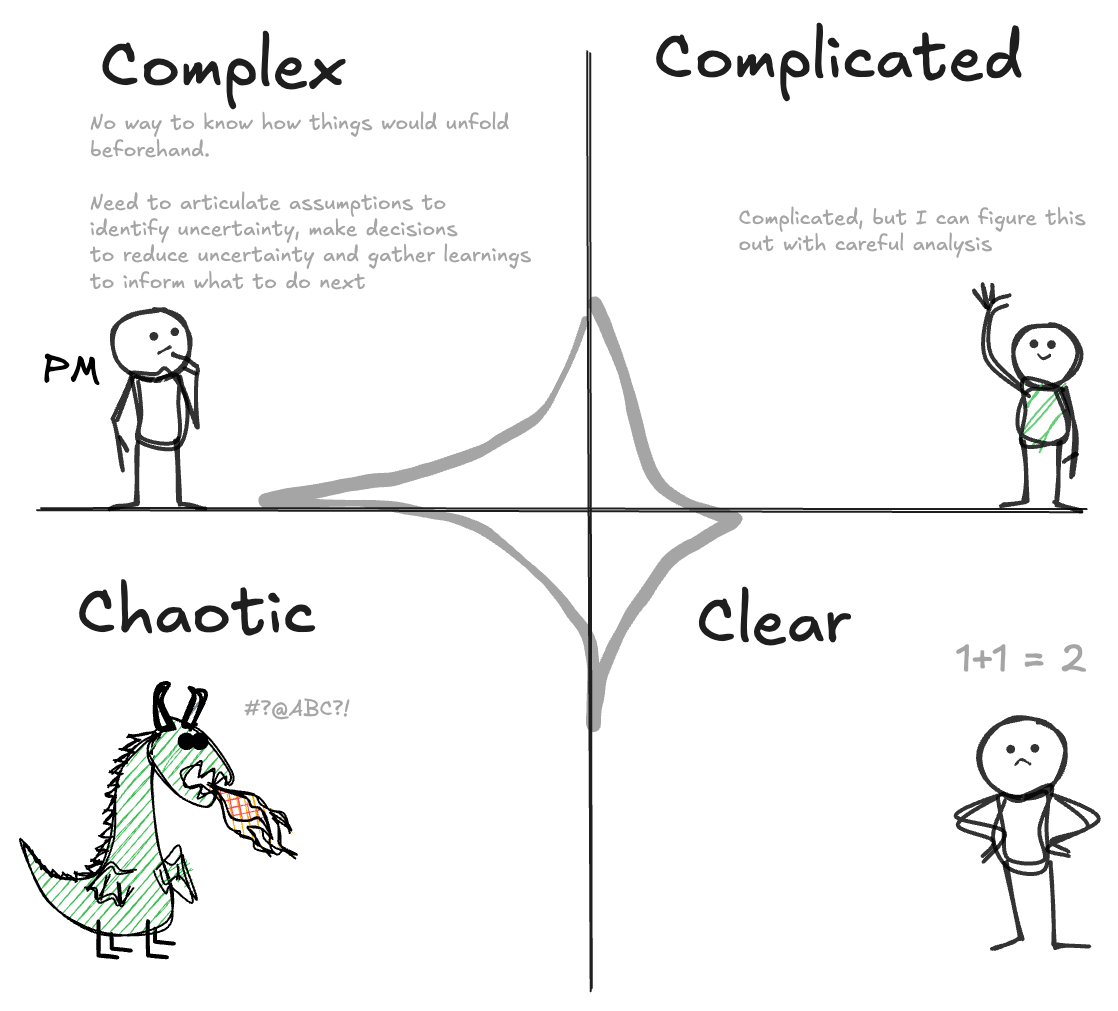

It was during a leisure walk when I arrived at a such a mental model. To be more precise, I was able to select out a particular framework that fits the need to make sense of this situation. The Cynefin framework - a sense-making model, distinguishes between complex problem domain and complicated problem domain. Complex problems are typically what PMs have to deal with, and this domain is characterized by the inherent difficulty of understanding cause & effects relationships beforehand.

The complex domain was also where our power user, the junior PM, had to operate in as she was making progress on her product initiative at work. It's also where most of the real-world messy product work take place in. You simply cannot sit down, analyze and predict accurately what's gonna happen or how users are gonna react. You often lack historical data when launching a new initiative or feature. According to Cynefin, the best move is to interact with the world to uncover information, cap your downsizes and see what patterns emerge.

But what about complicated problems? In a complicated problem domain, the relationship between cause & effect requires analysis and reductionism. In other words, you can analyze and see what works and what doesn't, instead of having to let the situation play out and observe its effects.

This leads to an important question: does working on BPM final projects count as a complicated problem? Interestingly, when I recalled the Cynefin framework during my walk, this question revealed the answer almost immediately. That's how it seemed in my mind, at least. Let me explain.

The interesting property of complicated problem domain - it's the domain of experts - those who can see the hidden patterns and quickly spot the relationship between one thing and another. We've mentored over 10 batches of BPM final projects, and while every batch is different, there are consistent patterns that lead to good project outcomes. You might say that we're something of an expert in this domain, although this is our students' first time doing this from their perspectives.

Back to Cynefin, it suggests that the dominant strategy to navigate complex problems is to listen to experts. Our students are already employing this strategy to some extent. As long as they put in the work, mentors can provide feedback on their output and help them course-correct as needed. This is already happening in the final project regardless of whether students are using Garden or not. However, since our students are new to Product Management and typically struggle to frame their thinking, we (mentors) have to do a bit extra work. Not only we have to evaluate their framings, but we also need to look at the raw data behind, in order to provide meaningful directions.

So back to the original question: how would Garden help create value for BPM starter students during the final project?

Garden might be useful for out students by providing them with built-in scaffoldings to help guide their thinking. Once they've put their assumptions and learnings into Garden, we also automatically gain visibility into their work on a granular level (versus dumping everything on Figma - great for brainstorming but terrible for structured thinking). This is my theory for how Garden would create value for our students during their final projects.

After this, we experimented Garden with several batches, and I've seen some early evidence that this might be true. In no way this is saying that I've cracked the code, unlocked the Pandora box and figured out PMF for my product. It's just that my mental model was generally in the right direction. But still it needed to be further refined. I won't bore you with the details though.

That's the trimmed version of my train of thought that was culminated on my leisure walk. If you find it convoluted, what went through my head at the time was much more so that I questioned my own insanity afterwards.

I just wanted to make a point though, that long thinking has really worked out for me. But why does long thinking work so well? There's one thing that's been lurking at the back of my head almost as soon as I started thinking about this question. It's the idea of tension.

Tension is the pathway to insights

Become comfortable with tension

I first encountered the idea of productive tension in Josh Waitzkin's "The Art of Learning." Waitzkin, a chess prodigy who later became a world champion in Tai Chi Push Hands, describes how he learned to be comfortable with tension and how it has played a central part in both of his competitive careers - chess and martial art. His achievement of mastery in two completely different sports really ought to make you pay attention to what he says. Here's one part (mong many) where he mentioned about tension:

The Art of Learning, by Josh Waitzkin

So tension, according to a world-class chess grandmaster and athlete, is something you should become comfortable with. This has been my experience as well (not to say that I'm world-class or anything). When I do long thinking, I have to consciously and constantly re-direct my attention back to a problem despite the lack of apparent progress. This is akin to maintaining a kind of tension within your own mental space, without releasing too easily and allowing your mind to wander to happier places that bring joy or comfort.

But why does tension during long thinking work better than just regular thinking? Below is my attempt to articulate a theory of why it works.

Tension, decompose & relax

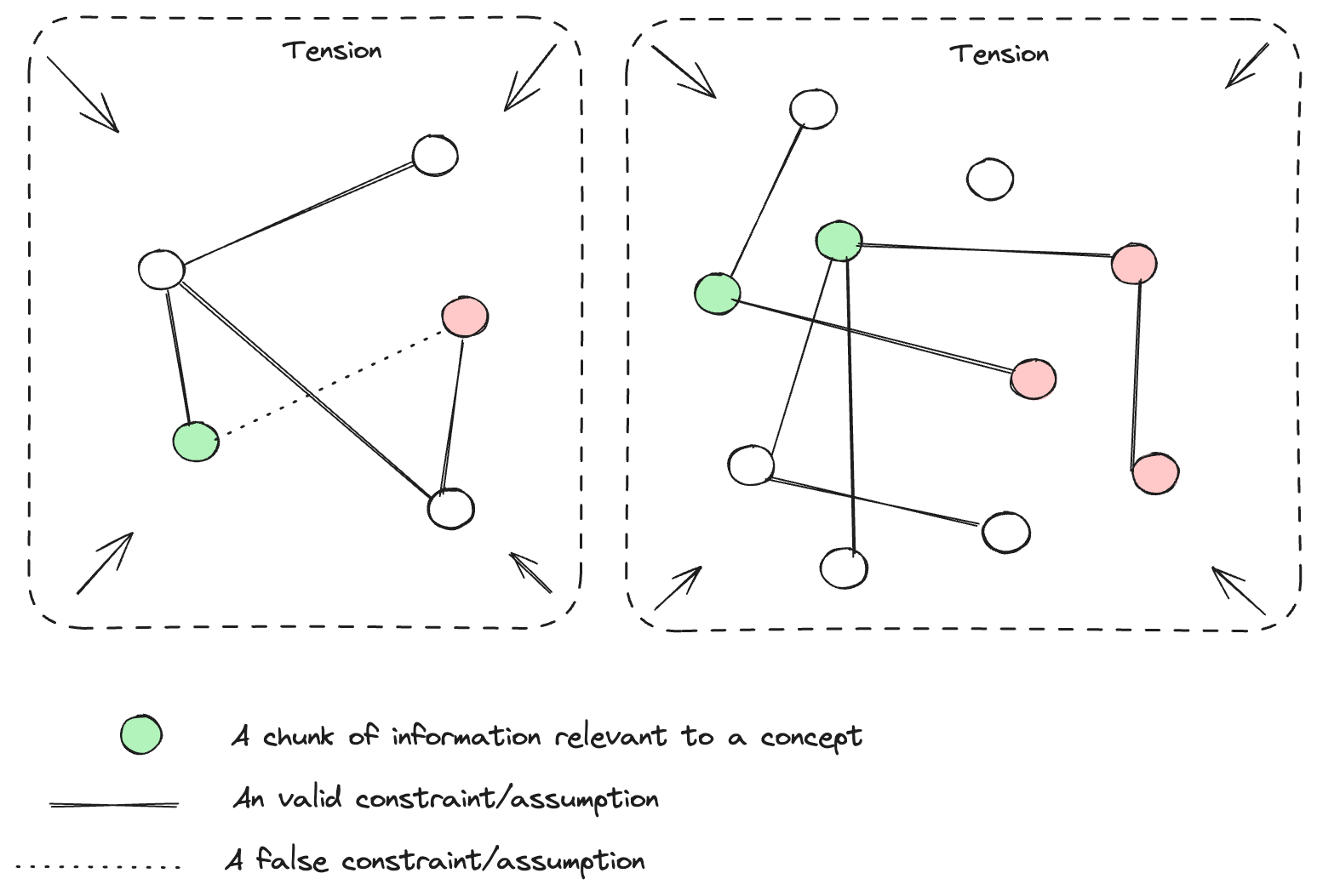

Whenever I think about tension, the image I conjure in mind always depicts two or more ideas. This is the first clue: tension always involves the relationships between two or more ideas. When I do long thinking, I have a central topic in mind, but the magic happens when I place it in context of other concepts and explore potential connections.

I suspect the act of conjuring this web of ideas and hold them in our mental headspace sufficiently long is the key to insights. When I apply pressure to that latticework of ideas, interesting effects take place: I decompose my ideas, and I relax invalid constraints/assumptions. Scientifically, these conditions have been known to play a central role in insightful problem-solving.

Let me dust off my scientific hat and pull up some research I've conducted years go into the field of insightful problem solving (which I briefly asked ChatGPT Deep Research if they still hold today; apparently yes, so do your due intelligence - trust but verify). Actually, I'll let ChatGPT provide you with an overview, instead of trying to be authentic and pretend I wrote this:

In this view, individuals impose unnecessary constraints or fixations—often unconsciously—that prevent them from seeing the solution. When standard strategies fail, the solver must reconfigure their mental model, either by relaxing constraints (removing assumptions that are not actually part of the problem) or by decomposing chunks (breaking down familiar elements into smaller, more manipulable components) (Ohlsson, 1992; Knoblich et al., 1999).

Empirical support for RCT has been especially strong in tasks that require perceptual or conceptual reorganization. For example, Knoblich, Ohlsson, Haider, and Rhenius (1999) demonstrated through matchstick arithmetic problems that insight often depends on the solver's ability to decompose visual “chunks” in unconventional ways.

Their findings showed that when problem components were grouped in typical patterns, participants often struggled—but when the grouping was novel or the solver restructured the problem, insight was more likely to occur. This process of representational change is seen as the cognitive mechanism behind the “Aha!” moment, offering a compelling account of why insight often feels sudden, surprising, and self-evident once achieved.

Source: ChatGPT (prompted by me)

Next, I want to use this scientific theory to speculate why applying pressure and maintaining tension works on a web of ideas to help us arrive at insights. Let us revisit the insight I had on my walk mentioned in the previous section, and look at it through the lens of Representational Change Theory,

What does "chunks" and "constraints" mean?

It’s worth explaining what I mean by “chunks” and “constraints,” because these terms can sound more technical than they really are.

A “chunk” is simply the way our minds bundle information together when something feels familiar. Instead of seeing five separate pieces, we compress them into one mental unit because it’s easier to reason about. The downside is that once things are chunked, we don’t usually question what’s inside that bundle.

A “constraint” works the same way but shows up as an assumption we quietly treat as true. Sometimes these constraints are legitimate; other times they’re just leftovers from a previous situation that don’t actually apply.

In product work, this happens all the time. We get used to thinking about users, problems, and solutions in certain packaged ways, and without noticing it, those packages start limiting what we’re able to see. So when I describe an insight forming through chunk decomposition or constraint relaxation, I’m essentially saying that my mind stopped grouping things the old way, loosened some assumptions I didn’t realize I was holding, and allowed a new interpretation of the situation to emerge.

What might have happened in my head on that walk

When I look back on that walk now, I’m quite sure something interesting happened in my head long before the conclusion appeared in words. If you examine it through the lens of Representational Change Theory - the framework that explains how insights actually form - it becomes clearer why the answer felt so sudden and obvious once it clicked.

Before the walk, the entire question of whether BPM students could benefit from Garden was bundled together in my mind as a single, almost self-evident assumption: BPM students are doing “product work,” therefore they must be operating in the same messy, uncertain, complex domain that junior PMs face in real companies. That implicit framing carried a few constraints I didn’t realize I was imposing: that the nature of the final project mirrors real-world uncertainty, that Garden’s value would map over directly, and that the students’ struggles were tied to the same kind of ambiguity our power user faced.

Something about recalling the Cynefin framework loosened that chunk. The moment I brought it back into working memory, I unintentionally relaxed one of the hidden constraints I had been operating under - namely, that all work related to Product Management - including learning about it, automatically lives in the complex domain. With that assumption no longer acting as a guardrail, a new question surfaced almost instantly: what if BPM final projects aren’t complex at all?

That single shift was enough to break apart the previously rigid conceptual bundle. Instead of thinking of “students doing product work” as one unit, my mind began separating the pieces: the students themselves, their level of experience, the structure of the final project, the role of mentors, and the nature of the problem domain.

The moment those elements stood apart, instead of being fused together, new relationships became visible. Suddenly it wasn’t about ambiguous cause-and-effect anymore; it was about novices (students) entering a domain where the patterns are known (the final project), the path to competence has been repeated many times (because we've observed these patterns across 10 batches), and the bottleneck isn’t uncertainty but the students’ ability to articulate their thinking clearly enough for mentors to guide them.

That restructuring is probably why the conclusion felt so clean the moment it appeared. Once the representation shifted from “students navigating complexity” to “students navigating a complicated domain with expert guidance,” everything snapped into place. Garden’s role wasn’t to reduce uncertainty for them; it was to scaffold their thinking so mentors could see the structure of their assumptions and help them course-correct faster.

And because that representation is more coherent than the one I unconsciously held before, the clarity arrived all at once, with that familiar sense of inevitability you get when something suddenly makes sense. Representational Change Theory would call that the moment the old chunk dissolved, the constraint fell away, and a new, more workable mental model took its place. In my experience, that’s exactly what it felt like.

Why holding off on releasing works

So why does holding on work? Representational Change Theory gives us part of the answer. When your first framing of a problem runs out of room, you feel it as tension. It’s the mind’s way of telling you that your current representation is failing. The pressure builds not because you’re doing something wrong, but because the old structure can’t accommodate all the information you’re trying to reconcile. If you release too early - by concluding prematurely or shifting your attention elsewhere - you never give your mind the chance to reorganize those pieces into a new, more workable structure. Insight has preconditions, and one of them is simply staying with the pressure long enough for the old representation to crack.

Another reason is that tension exposes the boundaries of your assumptions. When you sit with a problem beyond the point of comfort, you start noticing the quiet constraints you’ve been carrying. You see the default framings that were guiding your thinking without your awareness. That kind of noticing doesn’t happen in the first five minutes. It requires the slow grind of revisiting the same idea from slightly different angles until something no longer fits cleanly. The discomfort comes from that mismatch; the insight comes from resolving it in a more accurate way.

There’s also something mechanical about it. When you maintain tension, you’re forcing your mind to search - not linearly, but expansively. You begin recombining ideas, testing alternative framings, and making small conceptual moves that don’t seem meaningful on their own but eventually accumulate into a perspective shift. That process is inherently unstable and a bit chaotic. It takes time for the structure to collapse in the right place and re-form into something that suddenly makes sense. If you cut this process short, you interrupt the very dynamics that would have produced the breakthrough.

You should hold on a bit more when you feel like releasing

I have talked about how tension helps put pressure on your representation of a problem that might be flawed, so that its cracks reveal surprising insights. Now I want to talk about a few examples where people release the tension too early. The overarching theme is of course to say that you should hold on a bit more, precisely when you just feel like you need to release that pent-up tension.

The impulse to publish content

Our minds are wired to avoid the unsteady feeling of not knowing. When we feel uncomfortable, we seek an easy way out. We look for more comfortable things to do. There’s a particular moment in long thinking that I’ve come to recognize. It’s the moment when the pressure starts to feel slightly uncomfortable, when the ideas I’ve been circling for a while begin to lose their flavor, and a part of me wants to just let go. This impulse to release when pressure piles up is easily felt if you’ve ever written online. You probably know the urge to wrap up a half-formed thought and hit “Post” before it’s fully baked - not because you believe it’s ready, but because the act of completing it provides relief.

When I look at some of my past posts, I can tell which ones I released because a coherent framing emerged, and which ones I released because the tension of thinking was getting uncomfortable. The former always resonate more - not because the writing is better, but because the thinking behind it had time to mature. The latter usually read like a snapshot of my first reaction, missing the layers that only appear when you stay with a thought long enough to see its other sides. As a result, I tend to enjoy re-reading content that I thought long and hard about, compared to those that were pushed out prematurely.

When to release an MVP

This shows up in product teams too. I’ve seen teams rush features not because those features are the right next move, but because sitting in ambiguity is mentally taxing. It’s much easier to ship something, anything, to withstand the gnawing feeling of “we haven’t figured it out yet.” It creates a dopamine hit because you've checked something off the list, signifying that you can move on now. But the cost of that relief is real. You trade away the insight that might have surfaced if you had resisted the urge to prematurely resolve the problem.

This is a pretty tricky balance: you want to get early feedback, and releasing an MVP help you do that, but you also want to put a lot of thoughts into framing the hypothesis behind your MVP. Therein lies the sweet spot: after you've clearly articulated an assumption regarding how your MVP would create value for your users, it's probably time to release and get feedback, but not before.

This is not really a novel idea. The original intention of of MVP is a way to quickly gain validated learnings. Let's break it down: "learnings" obviously come from user feedback and product metrics. "Validated" learnings imply the existence of a hypothesis that you wanted to validate. It's easy to just release an MVP because now you can just vibe code a bunch of stuffs, but it's much harder to articulate a hypothesis behind why you believe your MVP would work and for whom. It's also much more rewarding when you finally see evidence that either solidify or modify your original thinking. However, that will not happen if you don't spend time articulating your hypothesis, and you (usually) won't know how to process feedback.

Conclusion

Holding on a bit longer builds a habit of confronting the moment right before insight emerges. You begin to recognize that the desire to release is not a sign of failure; it’s a sign that you’re getting close. The pressure means the old way of looking at things is reaching its limit. If you can tolerate that pressure for just a little more - whether that’s another five minutes of thinking during a walk, another pass over your reasoning, or another day sitting with a messy idea - you often find that the insight was sitting just past the point where you wanted to stop.

Over time, this becomes its own kind of craft: the ability to endure tension without letting it collapse prematurely. It’s a small, almost invisible discipline, but it’s the one that makes insight more likely. Not guaranteed, but more likely. And that alone is enough to make a noticeable difference in how often you arrive at good ideas, clear thinking, or better decisions.

You’ll probably notice, though, that long thinking doesn’t have to literally mean spending hours circling a problem in one continuous stretch. That’s great when you can do it, but it’s not a requirement. What matters is that you don’t fully release the tension. You can maintain it in smaller doses by returning to the same problem over time, letting it sit lightly at the back of your mind, revisiting it on a run, or turning it over once before bed.

As long as you don’t conclude prematurely and move on forever, the tension never fully dissipates - and that lingering pressure is often enough to keep the representational cracks open. In my experience, distributed long thinking works just as well as the multi-hour, monastic kind. Your mind will keep working on the problem in the background as long as you haven’t told it, “We’re done here.”

So the conclusion, for me, is simple:

That extra bit of patience is often the exact amount of time your mind needs to restructure the problem and uncover something useful. And if long thinking has taught me anything, it’s that those extra few minutes are where the good stuff usually lives.