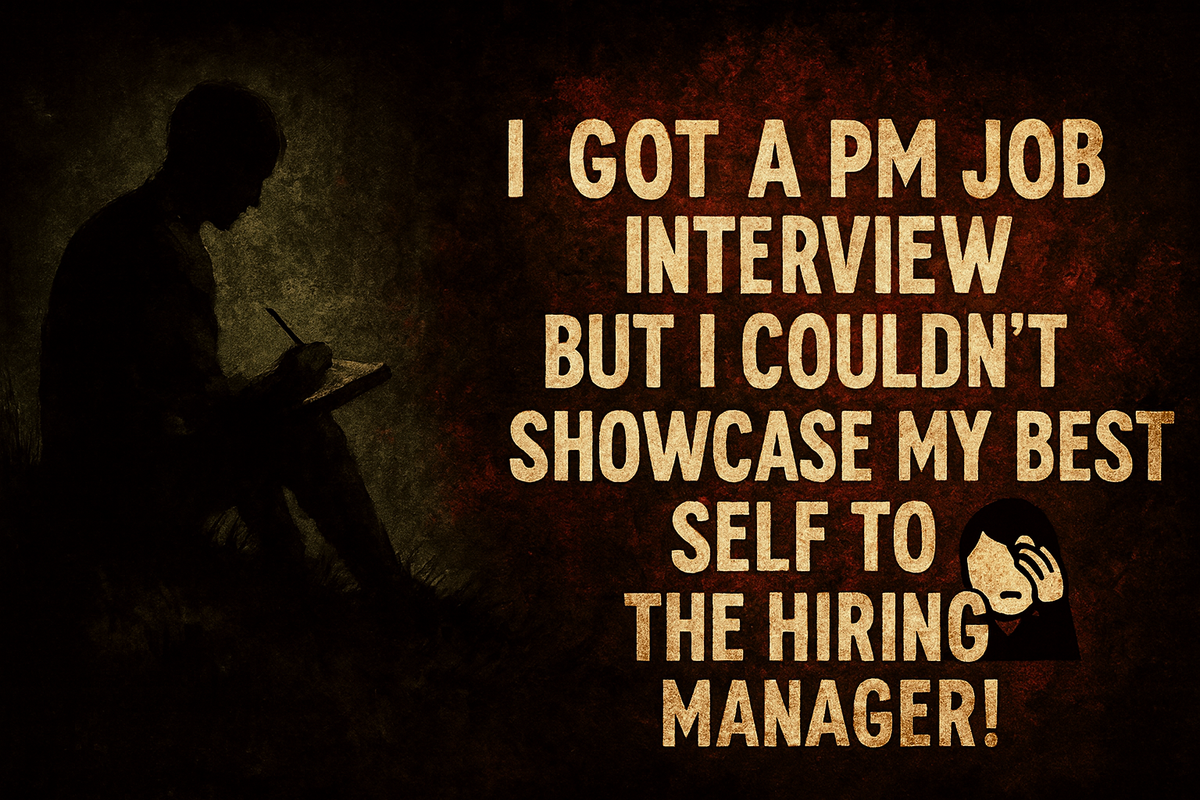

#51 - "I got a PM job interview but I couldn't showcase my best self to the hiring manager! 🤦"

Standing out as a Product Manager candidate isn’t about listing features you shipped. it’s about how you made decisions, tested assumptions, and adapted to what you learned. In this post, I share what hiring managers actually look for and how you can frame your stories to show real product judgment.

Do you ever feel like it’s impossible to stand out when applying for a Product Manager role? The competition is fierce, to put it mildly.

- If you’re a fresher or just graduating from college, you see it in the numbers - thousands of people applying for the same Product Management Trainee programs. I remember the odd for such programs was one versus twenty or something. It's natural to be overwhelmed - that number, in a sense, both quantifies and amplifies your anxiety.

- If you’re junior or mid-level professional, you might make it through the CV screen, but once you're in an interview, it’s still hard to show what makes you different. Maybe you don't know what a good answer looks like, or you're not able to craft a good story. To make things trickier, most hiring managers won’t give you detailed feedback, so you’re often blinded to what you could have done better.

As someone who's been on the other side of the table, I want to share what I actually look for in strong product candidates, and more importantly, how you can stand out by telling your story differently. In this first part of this series, I'll talk about how you can showcase your product work to hiring managers during an interview. In the second part, I'll share more about how to build an effective product portfolio.

👉 Struggling to stand out as a PM candidate?

That’s exactly the problem we’re tackling.

We’re building a product for aspiring and mid-career Product Managers who are tired of blending into the crowd. The goal: help you turn messy portfolio projects or product initiatives into clear stories that highlight your skills - and get you noticed. Along the way, you’ll receive expert feedback to sharpen your thinking and showcase your work with confidence.

The secret sauce? Using decisions, assumptions, and learnings as the backbone of your story - the same framework I’ve shared in this article.

We’re still in Alpha, which means I’m working closely with a small group of motivated early adopters to help them get real value from the product. If you’re serious about differentiating yourself in a crowded PM job market, I’d love for you to join us.

We all know of the following interview question, perhaps worded differently by different people:

"Tell me about a favorite project or feature that you delivered. How did it happen?"

On the surface, it looks straightforward: pick a feature, describe what it does, maybe explain how you delivered it using Scrum or Kanban. But if that’s all you tell me, I’ll politely listen, nod along, and then awkwardly move on to another question - while quietly feeling disappointed.

Yes, outcome over output is good but not enough

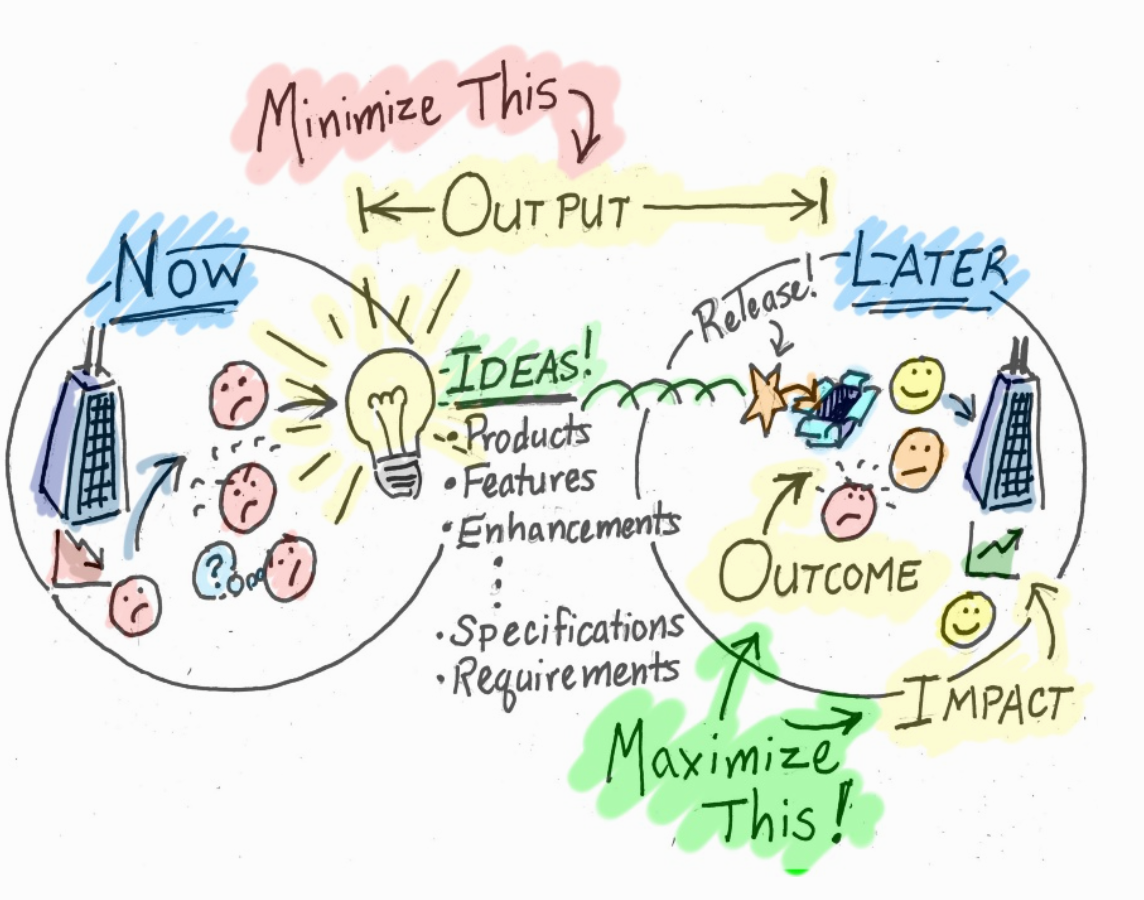

What is wrong with this answer? I'm going to use a reference from the book User Story Mapping. You probably have heard or read this book (it's amazing by the way), but I want to bring your attention to this particular diagram.

On the left, you see the world as it is today: people who are confused, frustrated, or struggling to get something done. Out of that, we generate ideas - new products, features, enhancements, requirements. Once those ideas get built and shipped, they turn into output.

But as the diagram makes clear, output is just the delivery step. What we really care about is what happens after release. That’s the outcome - how people’s behavior changes once they use what you’ve built, and whether you’ve actually made their lives better. And then, further downstream, you get the impact - the longer-term ripple effects like happier customers, increased revenue, reduced costs, or market expansion.

The message is simple: minimize output for its own sake, maximize outcome and impact. Which is why answers in interviews that stop at “we shipped this feature” miss the point - they’re stuck in the output bubble. It doesn't get at the heart of product development.

That said, let’s be real: “outcome over output” is a bit of a dead horse. You’ve probably heard this mantra already. And while outcomes and impacts are important, they’re also lagging indicators. They show up after the fact, and they’re shaped by many forces beyond your control - timing, competition, even luck. Which means that simply pointing to outcomes (“I tripled revenue!”) doesn’t necessarily demonstrate your product thinking.

This is especially risky if you’re a junior PM. Over-indexing on outcomes can make you sound naïve, because seasoned interviewers know how many factors influence results outside of one PM’s decisions. What they’re actually listening for is how you navigate the messy middle - the uncertainty before outcomes arrive.

So yes, talk about outcomes and impacts if you can. But don’t stop there. To stand out, go deeper: show me the inputs you controlled - the decisions you made, the assumptions you tested, the learnings you gained. This brings us to the next section: what does a good answer consist of?

Anatomy of a good answer

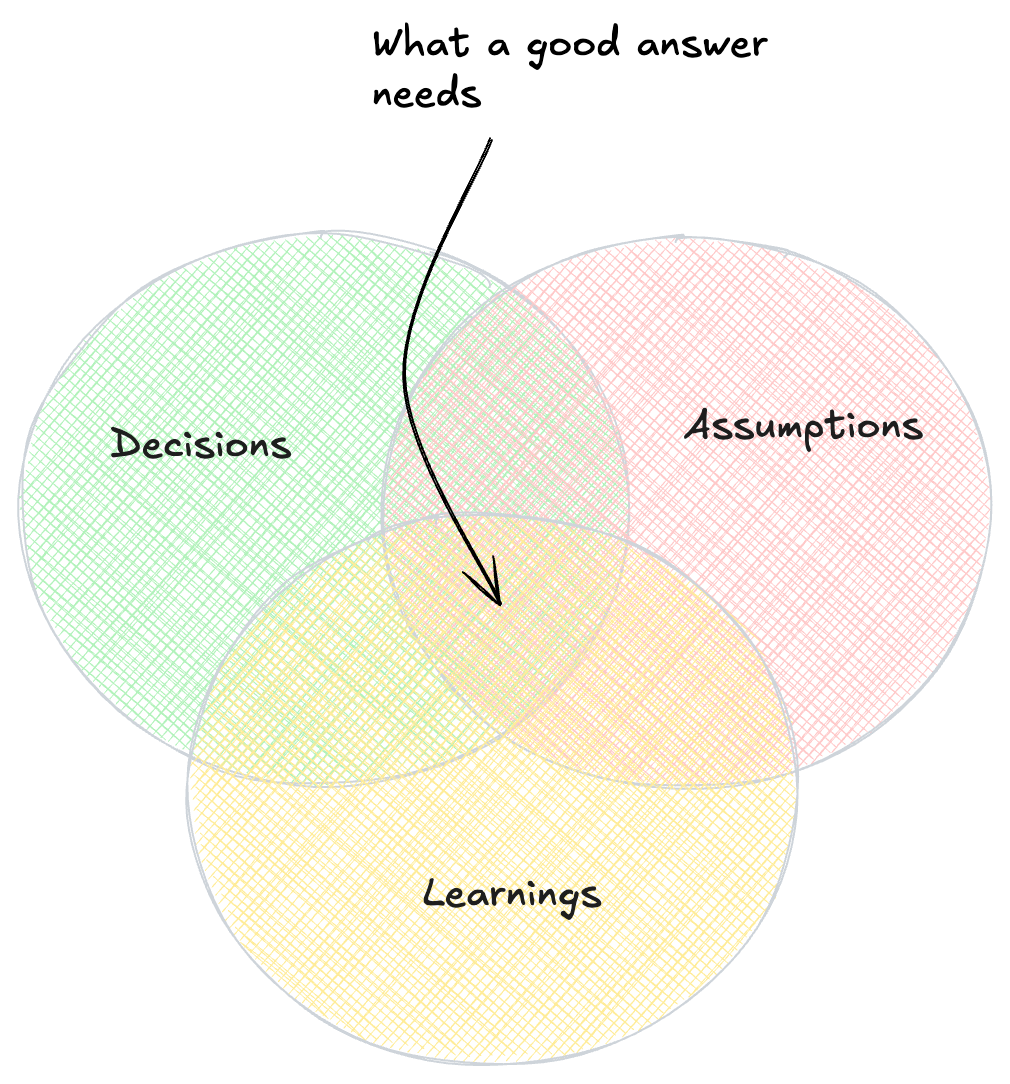

As mentioned above, I believe a good answer consists of three components:

- Decisions. What choices did you personally make, what were the trade-offs, what were difficult and why? I'm curious about how you were able to assess the situation and move it forward with incomplete information, more than I care about what the feature is or how it works, unless they provide valuable details to contextualize your decisions.

- Assumptions. What assumptions were baked into your decision-making? Which assumptions did you articulate beforehand, and which ones emerge after validations? Because you know what Mark Twain said: "It's not what you don't know that kills you, it's what you know for sure that just ain't so."

- Learnings. What did you learn from making decisions? How did you plan to validate your assumptions? Did you intentionally seek learnings while minimizing risks? I'm not interested in the "here's 3 lessons I learned after I delivered the feature" type of answer, I want to know what you learned and how it informed your decisions during the project.

Here's a simple diagram for those who are visually oriented:

Let's examine each component in detail, starting with decisions.

Your answer should demonstrate decision-making under uncertainty

What I look for in candidates first and foremost is how they're involved in shaping the product. That means I want to know the decisions that you made, not the ones that were instructed or prescribed. The feature itself is just a vessel. What matters is how you use it to show the choices you faced, the trade-offs during development, and how you iterated.

Take an example. Say your company decided to build an access management feature that allows admins to control who can view, edit, or delete documents. Don't start by telling me how the feature works, what kind of roles were there in the system, what were their permissions, so on and so forth. Save them for later.

First, focus on decisions: you might have received this brief from your boss, but then decided to validate the problem with customers through looking at support tickets, then brought in engineering to assess feasibility, then finally ran a pilot with early requesters before an official release. Those decisions let me know at a high-level how you were involved in the project. Also, I'm definitely gonna take some notes on your answers (I have to answer to HR and comply with the hiring process), so these decisions provide me with a good place to start. Helping me take good detailed notes helps with your assessment, because other hiring managers can and often do read them as part of their evaluation.

This is where frameworks can help. Most product management frameworks prescribe decisions. For example, Design Thinking tells you to empathize, define, ideate, prototype and finally test. Double Diamond tells you to go wide and narrow down on both problem space and solution space. These frameworks can definitely be useful as a starting point. However, if you just follow prescribed decisions, that's not a good answer (or good PM work).

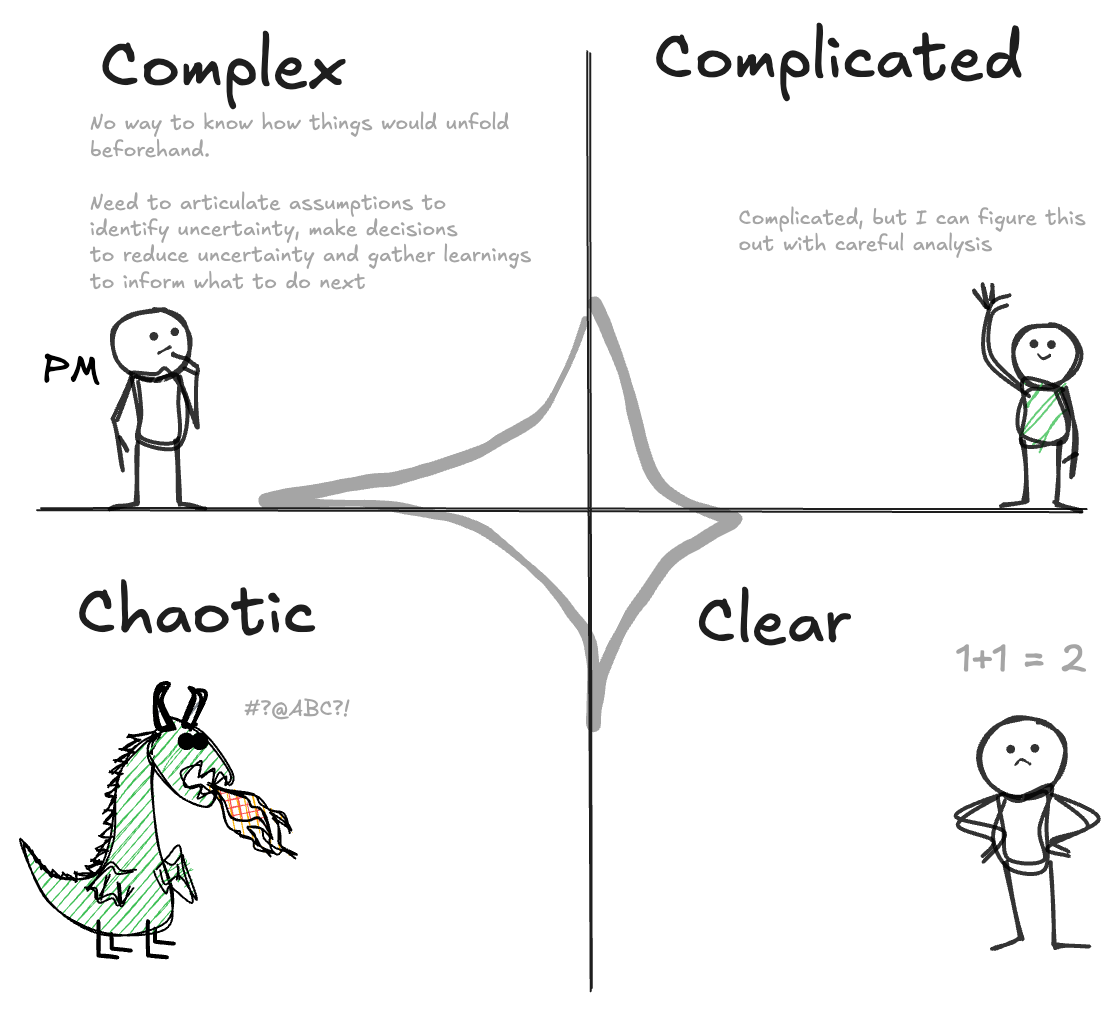

This is because Product Management as a discipline mostly has to deal with complex problems. I'm not talking about complexity in a generic sense, I'm talking about complexity as defined by the Cynefin framework - which is a way to classify context into different domains based on the relationships between cause-and-effect.

There are several domains in Cynefin that are worth describing:

- In a simple domain, cause and effect is clear, so you just need to apply best practices. Two plus two equals four, that type of things. Extremely low or no uncertainty. PMs don't typically get paid to solve simple problems. Not saying these are unimportant by the way, it's just that they are of a different nature than what PMs tend to deal with.

- In a complicated domain, cause and effect is not obvious, but can be revealed through analysis. You rely on good practices and expert judgement. There is uncertainty here, but they can be mostly eliminated with analysis.

- Think about the technical part of developing a feature. It's not simple. There is a lot moving pieces in a production-level system, but expert engineers can analyze and apply good judgement to solve these problems effectively.

- Not every engineering problem is complicated, some can even be complex - think about the very first big tech company that has to serve millions of requests per second, there's no analysis or expertise for that problem (at that time).

- 👉 In a complex domain, the relationship between cause and effect only becomes clear in retrospect. There is no way to know beforehand how things are going to unfold, so you have to cap your downsides, allow patterns to emerge and respond to them appropriately.

- This is the class of problems with very high degree of uncertainty. For example, there's really no way to know when you're building an access management feature wether or not it will lead better user retention. You can make an educated guess, but how your customers actually respond is the only source of truth. As PMs, this is the domain in which we frequently have to operate and navigate.

- To be clear, I'm not saying the PM job is more difficult than others just because we have to work with complex problems. Somebody has to do it, and it happens to be us. That said, we don't always manage to do it successfully (I know I failed a couple of times).

- There are other domains as well, but I'll spare you further details.

Anyway, here's a diagram that summarize domains as defined by Cynefin:

I'm not telling you about this framework just to show off my wealth of knowledge 👅. This classification allows us to talk about navigating uncertainty in a more meaningful way: in complex domains, you can’t plan everything ahead and expect reality to comply. Put it another way, you cannot just follow a linear decision-making framework, or a set of prescribed decisions, and hope to achieve any sort of meaningful outcomes. In this complex domain, decisions are made under uncertainty, and constantly reshaped.

For example, you may build the access management feature for mid-sized product companies, only to discover in Alpha testing that they don't really use it that much. Meanwhile, a completely unexpected segment, say marketing agencies, adopt the feature and use it quite often, because they need to protect client-facing documents and avoid accidental archives on inactive documents from junior employees.

Suddenly, your “decision to target mid-sized product companies” isn’t final at all. It’s reshaped by what you learn. So if your answer consists of just decisions, it's easy to gloss over the forces that shape them.

So what are the forces that shape our decisions?

Your answer should illuminate what shapes your decisions

What shapes decisions are two things: the assumptions you hold beforehand, and the learnings you gain afterwards.

This framing may be a bit extreme, but I believe that the majority of thoughts we have when building a product or a feature lean towards assumptions rather than cold hard truths. When you make a decision to focus on a particular customer segment, you're assuming a lot of things: this customer segment will adopt our feature, they'll keep buying from us or buy more from us as a result of using this feature, and their usage will translate into some forms of long-term competitive advantage. Any of these assumptions may turn out to be wrong. If not explicitly spelled out, you may not even realize when they're invalidated.

In the access management example, one assumption might have been: “Our mid-sized product company customers care deeply about access control for security and compliance. If we release this feature for them, we're going to see adoption starting with admins and expanding to all functions within three months.” This assumption guided your decision to build.

Then came the learnings: maybe the original requester barely used it (invalidating your first assumption), but marketing agencies loved it (revealing an unexpected opportunity). That learning pushed you to reposition the feature and refocus your go-to-market strategy. That's a much more compelling narrative compared to if you just talk about the feature itself.

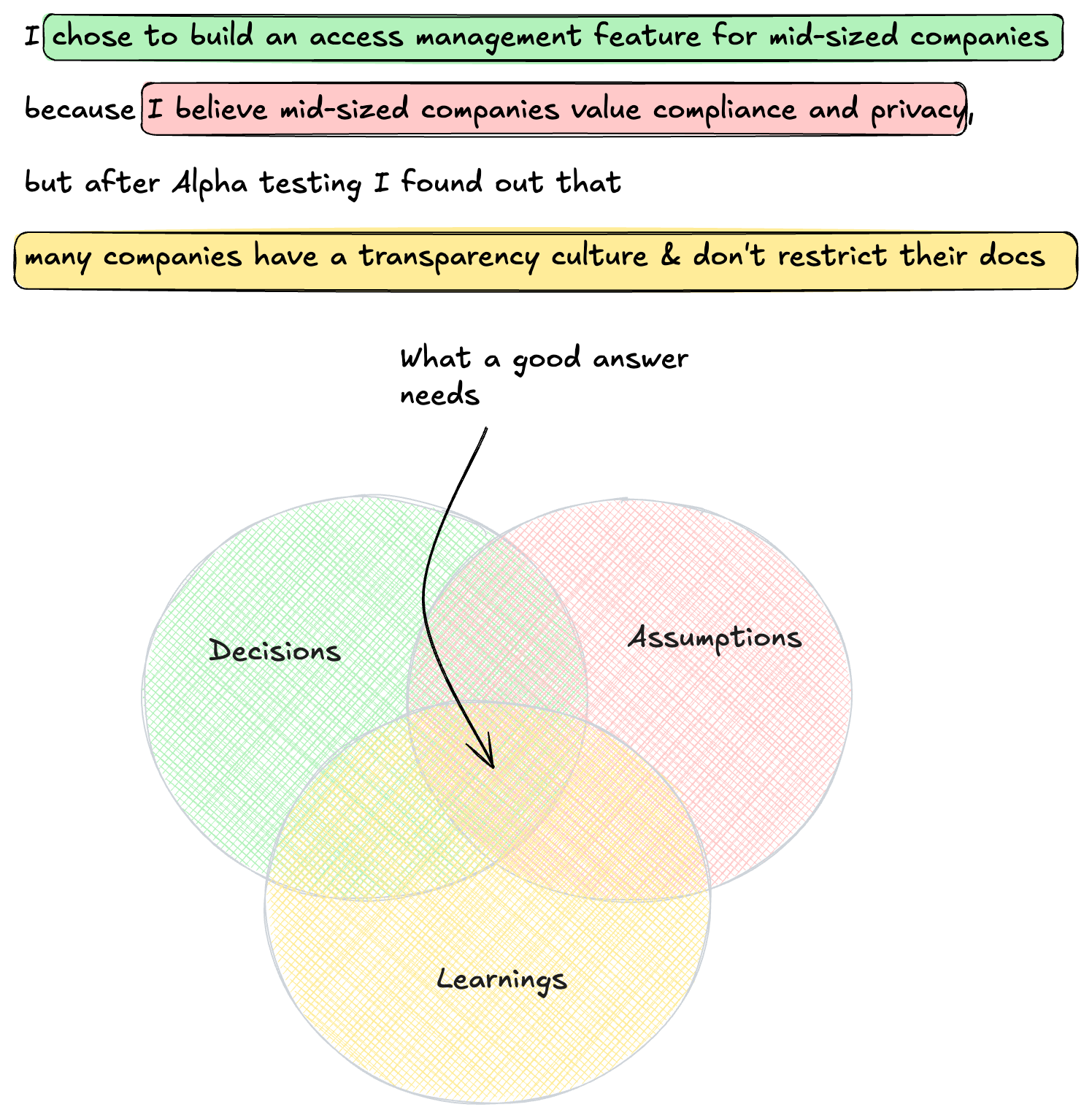

So when you answer that classic interview question, don’t just tell me about the feature. Tell me about the decisions you made, the assumptions that shaped them, and the learnings that reshaped the next decisions.

If you write down your answer beforehand, you can use color codes and make sure that these components are present.

How to articulate an assumption in a useful manner? What is considered a learning? I can write a whole essay on these topics, though maybe another time. But in short, nothing beats practice. If you're interested in practices that can increase your likelihood of successful job application or helps you level up as a junior Product Manager, we (BPM) are building a product that incorporates decisions, assumptions and learnings as guiding structure.

👉 Struggling to stand out as a PM candidate?

That’s exactly the problem we’re tackling.

We’re building a product for aspiring and mid-career Product Managers who are tired of blending into the crowd. The goal: help you turn messy portfolio projects or product initiatives into clear stories that highlight your skills - and get you noticed. Along the way, you’ll receive expert feedback to sharpen your thinking and showcase your work with confidence.

The secret sauce? Using decisions, assumptions, and learnings as the backbone of your story - the same framework I’ve shared in this article.

We’re still in Alpha, which means I’m working closely with a small group of motivated early adopters to help them get real value from the product. If you’re serious about differentiating yourself in a crowded PM job market, I’d love for you to join us.

What a good answer may look like

Okay, so I've talked about the components of a good answer and analyzed them separately. When we put them together, what would the answer look like?

Here's an example answer that incorporate decisions, assumptions and learnings. This combines various examples about the access management feature I mentioned before into a coherent answer:

"The next decision I made was to validate demand more broadly before rolling it out further. My assumption was that if one mid-sized product company asked for it, others in the same segment must be facing the same issue. We reached out to about ten companies in that profile. What we learned was mixed: a few cared, but most echoed the same sentiment - their teams were small and trusted enough that they didn’t bother with access restrictions. That taught me the demand wasn’t universal, and that if we were going to invest further, we needed to get sharper about who actually valued the feature."

"Finally, I decided to pilot the feature with a more diverse mix of companies, not just mid-sized product companies. The assumption was that adoption in our original target segment would validate the feature’s broader value. But the usage data told a different story: the mid-sized companies barely touched it, while two marketing agencies were logging into the admin panel multiple times a week. Curious, we interviewed those admins, and they told us why: they often shared documents with clients, and they needed to prevent junior staff from accidentally deleting or altering those files. That was a real, high-frequency pain point. The learning was that the strongest demand came from agencies, not the product companies we initially built for. That insight pushed us to reposition the feature toward agencies and later design our go-to-market messaging around protecting client deliverables."

Notice how this answer weaves the decisions (prioritization, validation, piloting), the assumptions (mid-sized companies care about compliance, request equals widespread demand), and the learnings (initial assumption invalidated, demand uneven, new segment revealed through usage data and interviews). This gives me, as a hiring manager, a full picture of how you navigate complexity - not just what you shipped.

The nice thing about this answer is that it's not generic. It doesn't mention any frameworks specifically, but you can gauge many things about the candidate's product discovery skills and customer understanding, through examining their decisions, assumptions and learnings. Note that this is a condensed example. If you're able to articulate more precise assumptions and describe how you gather learnings in more details, your answer would be even stronger.

A note on wording: you don't have to repeat "assumption", "decision" or "learning" like a broken record throughout the answer. Feel free to get creative with words. Assumptions are simply what you thought were true, decisions are choices that you make based on certain assumptions, and learnings are evidence that either increase or decrease your confidence in assumptions, sometimes enough to guide your next decisions.

Conclusion

To wrap up this blog post, you can leverage decisions, assumptions and learnings as guiding structure for your answer, in order to showcase how you navigate uncertainty to hiring managers when you get asked about a project or a feature that you worked on. Here's a fellow hiring manger for Product positions has to say on this topic:

I'm gonna go a bit meta here: I decided to write this blog post with the assumption that you're already getting past the CV round. However, from talking with many freshers and even junior candidates, I learned that some can't even differentiate themselves enough to get noticed. Therefore, I've decided to write another article for this target audience (see what I did there? I just used decisions, assumptions and learnings!). As you can see, I'm not using this structure to answer an interview question, I am using it to navigate my initiative (in this case, writing).

In the next part of this series, I'll be sharing how to approach building your product portfolio using decisions, assumptions and learnings, so that you can stand out from the crowd. If you know someone who's applying for Product roles, feel free to send them this article 😆 I think it'd be helpful for them.

👉 Struggling to stand out as a PM candidate?

That’s exactly the problem we’re tackling.

We’re building a product for aspiring and mid-career Product Managers who are tired of blending into the crowd. The goal: help you turn messy portfolio projects or product initiatives into clear stories that highlight your skills - and get you noticed. Along the way, you’ll receive expert feedback to sharpen your thinking and showcase your work with confidence.

The secret sauce? Using decisions, assumptions, and learnings as the backbone of your story - the same framework I’ve shared in this article.

We’re still in Alpha, which means I’m working closely with a small group of motivated early adopters to help them get real value from the product. If you’re serious about differentiating yourself in a crowded PM job market, I’d love for you to join us.